WORK-LIFE BALANCE

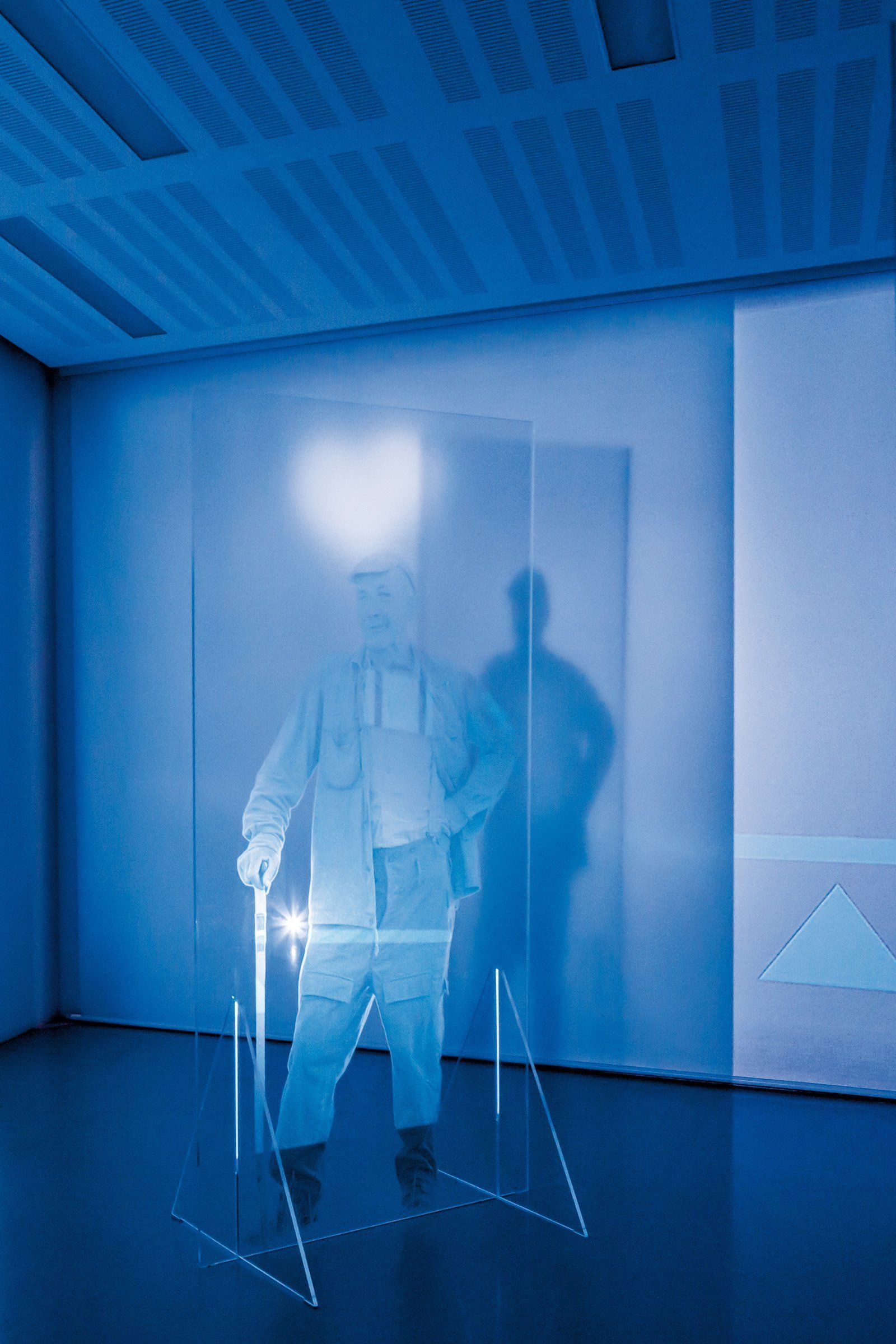

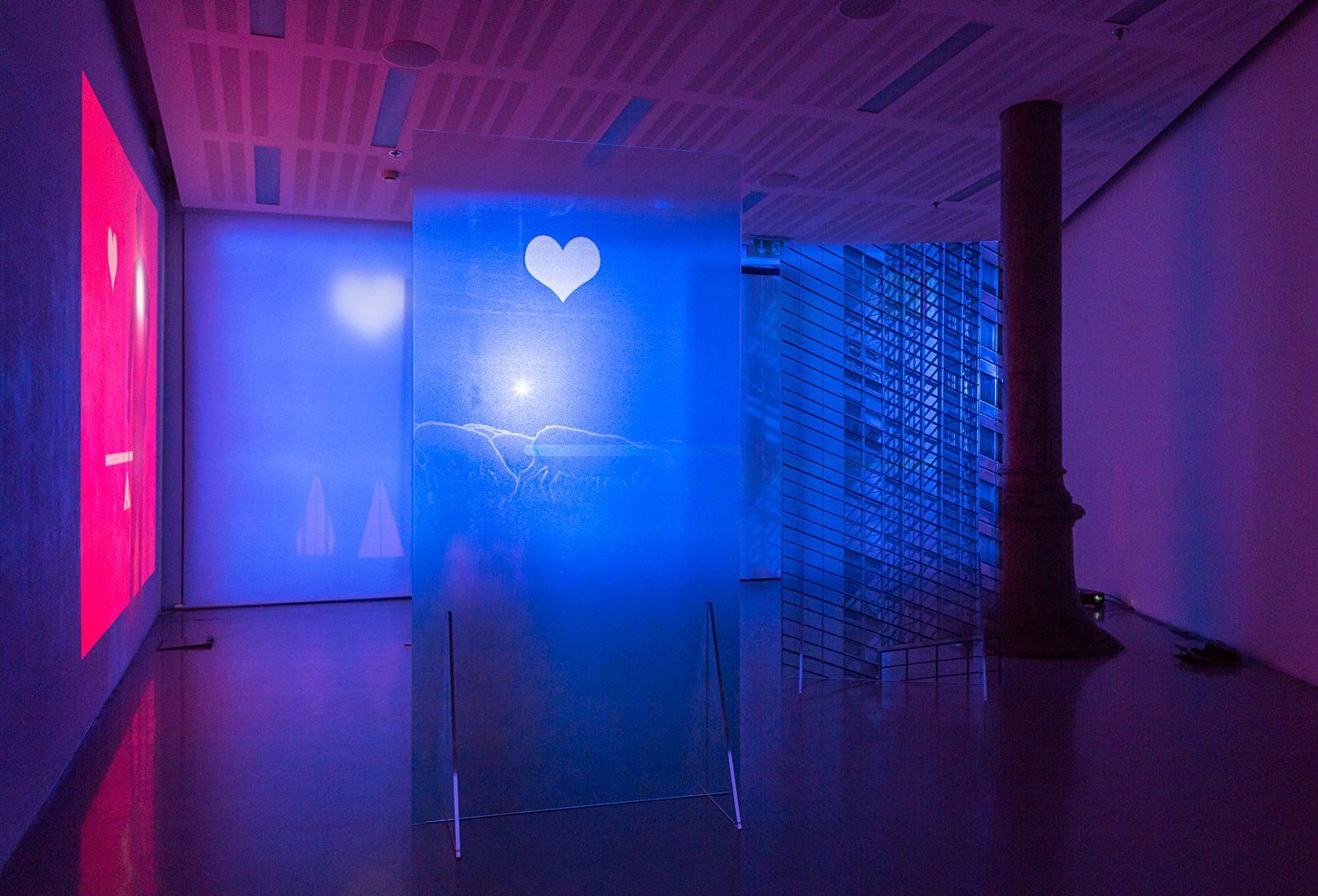

2018 / projection (2 channels) videoloop 3:57 min, UV print on acrylic glass, 1 x 2 m

The piece ‚Work-Life Balance’ refers to the past in order to speak about the contemporary issue of work-life balance. The aim of it is not to visualise a research or to deliver a socio-anthropological treatise, it is rather a conceptually based reaction to certain personages of Dadaism and avant-guardes of the 1920s and 1930s.

The term ‘work-life balance’ was coined in the 1980s, however, as a symptom of the late capitalism it can be traced deeply into the European history. The concept of work as a moral commandment and moral obligation has a long Christian tradition (the ‘ora et labora’ of the Benedictines) and it was accelerated in Protestantism. From the industrial era onwards, the unions developed strategies of how the workers could stop being objects and become subjects again. The dream of the welfare state (the division into 8 hours of work, 8 hours of active rest and 8 hours of passive rest) came to crisis in the 1980s and 1990s on the one hand with the collapse of the real socialism in the former so-called ‘Eastern Bloc,’ on the other hand with the dominance of the neoliberal worldview in Western societies. Work became ideology and religion, the institution/CEO was internalized into the workers. Therefore, it should not come as surprise that the term ‘work-life balance’ itself as a need for meaningful management of work time and leisure was first articulated in the 1980s.

The eponymous installation is intended to follow the transformation of the observation of social life and to awaken the aesthetics states associated with it.

It consists of large-format, UV-printed acrylic glass plates which serve as planes for the deconstruction of an emblematic GIF and transform this image into a picture space through reflections. The pictograms used in the GIF which should be understood as universal symbols, are based on the system of Otto Neurath’s ISOTYPE. Through their repetition, variation and decomposition, a specific dual system emerges.

The installation evolved from a previous work (Homage to the avant-guarde) in which the semi-transparent, small-format collages inspired by the graphic designs of László Moholy-Nagy and El Lissitzky. Both works (work-life balance and Homage to the avant-guarde) are connected by the usage of image as a matrix and a filter at the same time. The element of projection transforms the defined two-dimensional spaces into the undefined, immaterial spaces, to the collage of the real space with the projected image. The definition of the word ‘projection’ in Latin carries the meaning of planning and of ‘throwing into the future.’ In the piece Work-Life Balance, the scale is crucial: upon entering the installation, the spectator – or their shadow – becomes part of the work.

The installation as a (anti)order of the space brings a link to the Merzbau of Kurt Schwitters. His way of life combines two modes of work-life balance. As an artist, he worked in two shifts, one being creating art for art, the other one designing visuals for the industry and commerce. The dichotomy of his activities embodies the schizophrenia of capitalism which demands to be both crazy and serious at the same time. This has become now a common survival strategy. The work which he considered to be his life-time achievement – the Merzbau as a conglomeration of living space and an artwork, a fusion of work and privacy – can be seen as a role model for today’s working conditions, even outside the art world.

The photographic series of the Slovak documentary photographer of the interwar period, Irena Blühová, was meant to serve as a visual proof of the situation of rural working classes in the modernized regions of Czechoslovakia. Her initially socially critical view turned later into more ethnographic one, almost to an idyllic depiction of rural life. Using own photograph with the same motif of a shepherd from almost the same mountain area in northern Slovakia some 80 year after her updates this dream of the city about the physical work in the outdoors.

In his text Das Simultane oder Polykino László Moholy-Nagy welcomed the modern city, the diversity and simultaneity of the impulses and the technological progress which corresponds to the aesthetics of the modern human. The simultaneity of the impulses is already implemented in our society thanks to the technology and the relationship of humans and machines is considered as the central theme of contemporary discourses.

But let’s get back to the present, which can be understood as a future, once visualised by the artists mentioned above. Could the ‘today’ of the simultaneous occurrences, as Moholy-Nagy imagined it, the fusion of fun and work, be understood as a successful utopia? Do we live to work or do we work in order to live? Have we actually become happier or more effective?

(text by the artist)